Artist Biography

Leading Hudson River School Painter Famous for New England Views

By Amy J. Carvel

Painting in a unique style, Kensett became known as one of America’s most beloved landscape painters and luminists, as well as a founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I. Biography

II. Chronology

III. Collections

IV. Exhibitions

V. Memberships

VI. Notes

VII. Suggested Resources

I. Biography

John Frederick Kensett

Leading Hudson River School Painter Famous for New England Views

By Amy J. Carvel

Painting in a unique style, Kensett became known as one of America’s most beloved landscape painters and luminists, as well as a founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I. Biography

II. Chronology

III. Collections

IV. Exhibitions

V. Memberships

VI. Notes

VII. Suggested Resources

I. Biography

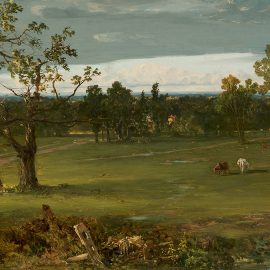

John Frederick Kensett was one of the most important artists of the Hudson River School, known for his poetic depictions of the American countryside. Born in Connecticut, Kensett trained under his father Thomas, an engraver, and began working in print shops in New Haven and New York in the 1830s. His career took flight after a seven-year sojourn in Europe, where he studied painting alongside John William Casilear and Asher B. Durand. Back in New York, Kensett turned his focus to American scenery, making sketching tours across the country. In 1849, the same year he was elected a full member of the National Academy of Design, he traveled with Casilear and Durand to the Catskill Mountains where the trio spent four months working in the woodland surrounding Thomas Cole’s former home. The expedition proved emblematic: Cole had died the year before, leaving a void at the Hudson River School that Kensett and Durand would soon fill.

Painting intimate landscapes that celebrated the American wilderness, Kensett came to lead the naturalistic (as opposed to Romantic) vein of the Hudson River School. He viewed nature as God’s own work of art and attempted to portray the wonder of divine creation in every rock and tree, capturing their texture and form through careful observation and inspired rendering. John Paul Driscoll, the leading Kensett scholar, emphasizes the tranquil nature of Kensett’s work, whose serenity “signals the poetry of his vision.”[1]

Initially celebrated for his woodland interiors and panoramic landscapes, Kensett turned to a limited register of sea and sky in the final decade of his life. Drawn from the landscapes of Lake George, Newport, and Contentment Island, his late work brought luminism to its zenith, heralding a new language of silence and repose. The luminist movement expressed the transcendental beliefs of Ralph Waldo Emerson in pictorial form, allowing the viewer to behold the universality and infinity of nature.2 The abstracting impulse visible in Kensett’s late work articulates the universality of natural form through a metaphysical transcendence of the specific scene; the emphasis is on pictorial shape rather than physical weight, silhouette instead of volume—stripping landscape to its essential impression. With delicate brushwork, elegant designs, and subtle tonal orders, Kensett put forward his vision of the harmony found in nature—the harmony of “stopped motion, silence, and stability.”[2]

Remarkable for his intelligent mind and generous temperament, Kensett was—both personally and professionally—one of the most influential artists of the Hudson River School. His reputation as a sensitive soul was so thoroughly established that it came to pervade discussions of his work. In his Book of the Artists, Henry T. Tuckerman concluded that:

[t]he calm sweetness of Kensett’s best efforts, the conscientiousness with which he preserves local diversities—the evenness of manner, the patience in detail, the harmonious tone—all are traceable to the artist’s feeling and innate disposition, as well as to his skill.[3]

Such descriptions dominated American art publications until Kensett’s death in 1872. The tragic circumstances surrounding the event supplied a fitting coda to his heroic life: the artist fell victim to pneumonia after attempting to save a drowning woman off the shore of the inaptly named Contentment Island.

Kensett was one of the leaders of the American art scene: he served on the Art Commission of the U.S. Capitol Building and was a founder of the Artists Fund Society and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met held a special retrospective on the artist in 1986; today his work is collected by every major museum, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the White House.

II. Chronology

1816 Born in Cheshire, CT on March 2nd

1829 Worked in the shop of printmaker Peter Maverick in New York and possibly with John Casilear

1832 Worked for Daggett and Ely, New Haven engravers; Applied to be an apprentice to Asher B. Durand, but was refused

1838 Worked for banknote engravers in Albany and exhibited first landscape painting at the National Academy of Design (simply titled Landscape)

1840 Traveled to England and France where he was in the company of artists including

Thomas Rossiter; Studied paintings at the Louvre and landscapes at Fontainebleau

1842 Met Thomas Cole in Paris and sent two landscapes to the National Academy exhibition

1843 Continued to live in England; Sold two paintings sent to New York and continued sketching at Hampstead, Richmond Hill, Windsor Forest, and other areas of the English countryside

1844 Went on tour with Champney up the Rhine, through Switzerland, and to Italy; Spent winter in Rome

1845 Sold eight paintings to the American Art-Union; Spent summer and early fall sketching in the campagna south and west of Rome

1846 Returned to New York in November

1847 Obtained studio in New York University Building; Elected an Associate of the National Academy and sold numerable landscapes to the Art-Union

1848 Elected full member of National Academy and the Century Association

1849 Elected to the Council of the National Academy of Design and a member of the Sketch Club

1850 Painted in Ohio, upstate New York, Niagara Falls, Green Mountains, Berkshires, Franconia Notch, and North Conway

1851 Took a room with Louis Lang, who would become his life-long roommate; Provided illustrations for George Curtis’s Lotus-Eating

1852 Summer trip to the Mississippi River, Genesee Valley, and Newport

1853 Possibly hiked to Mount Katahdin with Frederic Church; At Newport

1854 Traveled to England and Scotland

1859 Appointed to U.S. Capitol Art Commission

1862 Worked for eighteen months on Capitol Art Commission

1863 Summered at Newport

1864 Organized the Sanitary Fair exhibition; Summered at Newport

1870 Traveled with Sanford Gifford and Worthington Whittredge to Colorado and the Rockies; A founder and trustee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1872 Painted thirty-eight sketches known as “The Last Summer’s Work”; Contracted pneumonia trying to save the drowned wife of painter Vincent Colyer and died of heart failure in his studio December 14th

III. Collections

Addison Gallery of American Art, MA

Art Institute of Chicago, IL

Brooklyn Museum of Art, NY

Butler Institute of American Art, OH

Carnegie Museum of Art, PA

Cleveland Museum of Art, OH

Dallas Museum of Art, TX

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, CA

Harvard University Art Museum, MA

Hunter Museum of American Art, TN

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA

Maier Museum of Art, VA

Mead Art Museum, Amherst, MA

Milwaukee Art Museum, WI

Montclair Art Museum, NJ

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX

National Academy of Design, NY

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

New-York Historical Society, NY

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, IL

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain

IV. Exhibitions

1830–60 National Academy of Design

1852–69 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

1861–73 National Academy of Design

1861–84 Brooklyn Art Association

1873 National Academy of Design, memorial exhibition

1874–76 Boston Art Club

1986 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, retrospective

V. Memberships

Artists’ Fund Society, founder

Century Association

National Academy of Design

Metropolitan Museum of Art, founder

Sketch Club

Union League Club

VI. Notes

1. John Paul Driscoll, “From Burin to Brush,” in John Paul Driscoll and John K. Howat, John Frederick Kensett: An American Master (New York and London: Worcester Art Museum, in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1985), 70.

2. Barbara Novak, “Introduction: Nature’s Art,” in Nineteenth Century American Painting (New York: Artabras, in association with the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, 1986), 27–30.

3. Henry T. Tuckerman, cited in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, “The Last Summer’s Work,” in Driscoll and Howat, John Frederick Kensett: An American Master, 155–6.

VII. Suggested Resources

Driscoll, John Paul and John K. Howat. John Frederick Kensett: An American Master. New York and London: Worcester Art Museum in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1985.

Driscoll, John Paul. John F. Kensett Drawings. University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Museum of Art, 1978.

Howat, John K. John Frederick Kensett, 1816–1872. New York: American Federation of Arts, 1968.

John Frederick Kensett Papers, 1806–1896. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

“Kensett and the White Mountains,” Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Mass., http://www.wellesley.edu/DavisMuseum/collections/kensettv3.swf.

Olyphant, Robert M. “Installation views of the John Frederick Kensett Memorial Exhibition, National Academy of Design, March 24-29,[1873].” http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/collection/olyprobe.htm

Trafton, Melissa Geisler. “Critics, Collectors, and the Nineteenth-Century Taste for the Paintings of John Frederick Kensett.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2003.

Leading Hudson River School Painter Famous for New England Views

By Amy J. Carvel

Painting in a unique style, Kensett became known as one of America’s most beloved landscape painters and luminists, as well as a founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I. Biography

II. Chronology

III. Collections

IV. Exhibitions

V. Memberships

VI. Notes

VII. Suggested Resources

I. Biography

John Frederick Kensett was one of the most important artists of the Hudson River School, known for his poetic depictions of the American countryside. Born in Connecticut, Kensett trained under his father Thomas, an engraver, and began working in print shops in New Haven and New York in the 1830s. His career took flight after a seven-year sojourn in Europe, where he studied painting alongside John William Casilear and Asher B. Durand. Back in New York, Kensett turned his focus to American scenery, making sketching tours across the country. In 1849, the same year he was elected a full member of the National Academy of Design, he traveled with Casilear and Durand to the Catskill Mountains where the trio spent four months working in the woodland surrounding Thomas Cole’s former home. The expedition proved emblematic: Cole had died the year before, leaving a void at the Hudson River School that Kensett and Durand would soon fill.

Painting intimate landscapes that celebrated the American wilderness, Kensett came to lead the naturalistic (as opposed to Romantic) vein of the Hudson River School. He viewed nature as God’s own work of art and attempted to portray the wonder of divine creation in every rock and tree, capturing their texture and form through careful observation and inspired rendering. John Paul Driscoll, the leading Kensett scholar, emphasizes the tranquil nature of Kensett’s work, whose serenity “signals the poetry of his vision.”[1]

Initially celebrated for his woodland interiors and panoramic landscapes, Kensett turned to a limited register of sea and sky in the final decade of his life. Drawn from the landscapes of Lake George, Newport, and Contentment Island, his late work brought luminism to its zenith, heralding a new language of silence and repose. The luminist movement expressed the transcendental beliefs of Ralph Waldo Emerson in pictorial form, allowing the viewer to behold the universality and infinity of nature.2 The abstracting impulse visible in Kensett’s late work articulates the universality of natural form through a metaphysical transcendence of the specific scene; the emphasis is on pictorial shape rather than physical weight, silhouette instead of volume—stripping landscape to its essential impression. With delicate brushwork, elegant designs, and subtle tonal orders, Kensett put forward his vision of the harmony found in nature—the harmony of “stopped motion, silence, and stability.”[2]

Remarkable for his intelligent mind and generous temperament, Kensett was—both personally and professionally—one of the most influential artists of the Hudson River School. His reputation as a sensitive soul was so thoroughly established that it came to pervade discussions of his work. In his Book of the Artists, Henry T. Tuckerman concluded that:

[t]he calm sweetness of Kensett’s best efforts, the conscientiousness with which he preserves local diversities—the evenness of manner, the patience in detail, the harmonious tone—all are traceable to the artist’s feeling and innate disposition, as well as to his skill.[3]

Such descriptions dominated American art publications until Kensett’s death in 1872. The tragic circumstances surrounding the event supplied a fitting coda to his heroic life: the artist fell victim to pneumonia after attempting to save a drowning woman off the shore of the inaptly named Contentment Island.

Kensett was one of the leaders of the American art scene: he served on the Art Commission of the U.S. Capitol Building and was a founder of the Artists Fund Society and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met held a special retrospective on the artist in 1986; today his work is collected by every major museum, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the White House.

II. Chronology

1816 Born in Cheshire, CT on March 2nd

1829 Worked in the shop of printmaker Peter Maverick in New York and possibly with John Casilear

1832 Worked for Daggett and Ely, New Haven engravers; Applied to be an apprentice to Asher B. Durand, but was refused

1838 Worked for banknote engravers in Albany and exhibited first landscape painting at the National Academy of Design (simply titled Landscape)

1840 Traveled to England and France where he was in the company of artists including

Thomas Rossiter; Studied paintings at the Louvre and landscapes at Fontainebleau

1842 Met Thomas Cole in Paris and sent two landscapes to the National Academy exhibition

1843 Continued to live in England; Sold two paintings sent to New York and continued sketching at Hampstead, Richmond Hill, Windsor Forest, and other areas of the English countryside

1844 Went on tour with Champney up the Rhine, through Switzerland, and to Italy; Spent winter in Rome

1845 Sold eight paintings to the American Art-Union; Spent summer and early fall sketching in the campagna south and west of Rome

1846 Returned to New York in November

1847 Obtained studio in New York University Building; Elected an Associate of the National Academy and sold numerable landscapes to the Art-Union

1848 Elected full member of National Academy and the Century Association

1849 Elected to the Council of the National Academy of Design and a member of the Sketch Club

1850 Painted in Ohio, upstate New York, Niagara Falls, Green Mountains, Berkshires, Franconia Notch, and North Conway

1851 Took a room with Louis Lang, who would become his life-long roommate; Provided illustrations for George Curtis’s Lotus-Eating

1852 Summer trip to the Mississippi River, Genesee Valley, and Newport

1853 Possibly hiked to Mount Katahdin with Frederic Church; At Newport

1854 Traveled to England and Scotland

1859 Appointed to U.S. Capitol Art Commission

1862 Worked for eighteen months on Capitol Art Commission

1863 Summered at Newport

1864 Organized the Sanitary Fair exhibition; Summered at Newport

1870 Traveled with Sanford Gifford and Worthington Whittredge to Colorado and the Rockies; A founder and trustee of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1872 Painted thirty-eight sketches known as “The Last Summer’s Work”; Contracted pneumonia trying to save the drowned wife of painter Vincent Colyer and died of heart failure in his studio December 14th

III. Collections

Addison Gallery of American Art, MA

Art Institute of Chicago, IL

Brooklyn Museum of Art, NY

Butler Institute of American Art, OH

Carnegie Museum of Art, PA

Cleveland Museum of Art, OH

Dallas Museum of Art, TX

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, CA

Harvard University Art Museum, MA

Hunter Museum of American Art, TN

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, CA

Maier Museum of Art, VA

Mead Art Museum, Amherst, MA

Milwaukee Art Museum, WI

Montclair Art Museum, NJ

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX

National Academy of Design, NY

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

New-York Historical Society, NY

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, IL

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain

IV. Exhibitions

1830–60 National Academy of Design

1852–69 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

1861–73 National Academy of Design

1861–84 Brooklyn Art Association

1873 National Academy of Design, memorial exhibition

1874–76 Boston Art Club

1986 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, retrospective

V. Memberships

Artists’ Fund Society, founder

Century Association

National Academy of Design

Metropolitan Museum of Art, founder

Sketch Club

Union League Club

VI. Notes

1. John Paul Driscoll, “From Burin to Brush,” in John Paul Driscoll and John K. Howat, John Frederick Kensett: An American Master (New York and London: Worcester Art Museum, in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1985), 70.

2. Barbara Novak, “Introduction: Nature’s Art,” in Nineteenth Century American Painting (New York: Artabras, in association with the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, 1986), 27–30.

3. Henry T. Tuckerman, cited in Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, “The Last Summer’s Work,” in Driscoll and Howat, John Frederick Kensett: An American Master, 155–6.

VII. Suggested Resources

Driscoll, John Paul and John K. Howat. John Frederick Kensett: An American Master. New York and London: Worcester Art Museum in association with W. W. Norton & Company, 1985.

Driscoll, John Paul. John F. Kensett Drawings. University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Museum of Art, 1978.

Howat, John K. John Frederick Kensett, 1816–1872. New York: American Federation of Arts, 1968.

John Frederick Kensett Papers, 1806–1896. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

“Kensett and the White Mountains,” Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Mass., http://www.wellesley.edu/DavisMuseum/collections/kensettv3.swf.

Olyphant, Robert M. “Installation views of the John Frederick Kensett Memorial Exhibition, National Academy of Design, March 24-29,[1873].” http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/collection/olyprobe.htm

Trafton, Melissa Geisler. “Critics, Collectors, and the Nineteenth-Century Taste for the Paintings of John Frederick Kensett.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2003.